- Home

- Emily C A Snyder

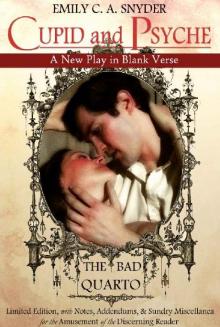

Cupid and Psyche

Cupid and Psyche Read online

CUPID and PSYCHE –

A New Play in Blank Verse

Emily C. A. Snyder

© 2014

Emily C. A. Snyder

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Cover photo © Emily C. A. Snyder

Actors: James Parenti as Cupid and Sarah Hankins as Psyche

For more information:

Cupid and Psyche

www.cupidandpsyche.net

Turn to Flesh Productions

www.turntoflesh.com

Emily C. A. Snyder

www.emilycasnyder.com

Copyright Information

Cupid and Psyche ~ A New Play in Blank Verse (First Edition: January 20, 2014)

Copyright © 2014 Emily C. A. Snyder

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Copyright Protection. This play (the “Play”) is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America and all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations, whether through bilateral or multilateral treaties or otherwise, and including, but not limited to, all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, and the Berne Convention.

Reservation of Rights. All rights to this Play are strictly reserved, including, without limitation, professional and amateur stage performance rights; motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video, and sound recording rights; rights to all other forms of mechanical or electronic reproduction now known or yet to be invented, such as CD-ROM, CD-I, DVD, photocopying, and information storage and retrieval systems; and the rights of translation into non-English languages.

Performance Licensing and Royalty Payments. Professional, amateur, and stock performance rights to this Play are controlled exclusively by Emily C. A. Snyder (the “Author”). No professional, amateur, or stock production groups or individual may perform this play without obtaining written permission from the Author. Required royalty fees may be subject to change without notice. Although this book may have been obtained for a particular licensed performance, such performance rights, if any, are not transferable. Required royalties must be paid every time the Play is performed before any audience, whether or not it is presented for profit and whether or not admission is charged. All licensing requests and inquiries concerning professional, amateur, and stock performance rights should be addressed to the Author via her production company, Turn to Flesh Productions: [email protected].

Restriction of Alterations. There shall be no deletions, alterations, or changes of any kind made to the Play, including the changing of character gender, the cutting of dialogue, the cutting of music, or the alteration of objectionable language, unless directly authorized by the Author. The title of the Play shall not be altered.

Author Credit. Any individual or group receiving permission to produce this Play is required to give credit to the Author as the sole and exclusive author of the Play. This obligation applies to the title page of every program distributed in connection with performance of the Play, and in any instance that the title of the Play appears for purposes of advertising, publicizing, or otherwise exploiting the Play and/or a production thereof. The name of the Author must appear on a separate line, in which no other name appears, immediately beneath the title and of a font size at least 50% as large as the largest letter used in the title of the Play. No person, firm, or entity may receive credit larger or more prominent than that accorded the Author. The name of the Author may not be abbreviated or otherwise alter from the form in which it appears in this Play.

Prohibition of Unauthorized Printing/Copying. Any unauthorized printing and/or copying of this book or excerpts from this book is strictly forbidden by law. Except as otherwise permitted by applicable law, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means now known or yet to be invented, including, without limitation, photocopying, printing, or scanning, without prior permission from the Author.

Exceptions include reviewers, who may quote brief passages in their reviews. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to the Author via [email protected].

Piracy. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Information

Table of Contents

PART ONE: INTRODUCTION

The Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Quarto

Writing in Verse

In Bed with Billy Shakes

How Not To Be Dun Edumicated

Never Underestimate the Power of Fingerpaint

The Rules of Blank Verse

Reviving the Renaissance

VERSE TRAPS (And How to Avoid Them)

VERSE TRAP 1: Content Dictates Form

VERSE TRAP 2: Stuck in Iambic With You

VERSE TRAP 3: Prosody

VERSE TRAP 4: Ding, Dong, Churchill’s Dead!

VERSE TRAP 5: Too Much Poetry, Not Enough Person

[Extended Speech] “Take Aim”

VERSE TRAP 6: ‘Til the Philosophers are Playwrights

[Deleted Speech] “A god of Passions—aye!”

VERSE TRAP 7: Stuck on Shakespeare

On This Edition and Endnotes

PART TWO: The Play

Persons of the Play

Workshop and Performance History

Acknowledgements

Dedication

Act I, Scene 1

Act II, Scene 1

Act III, Scene 1

Act III, Scene 2

Act III, Scene 3

Act III, Scene 4

Act IV, Scene 1

Act IV, Scene 2

Act IV, Scene 3

Act IV, Scene 4

Act IV, Scene 5

Act V, Scene 1

Act V, Scene 2

PART THRE: ENDNOTES

SECTION 1: MISCELLANEA

Two Noble Kinsmen

Alas, Poor Irina!

Belovèd-èd-èd-èd-èd

“What Should I Say?”

Adonis and Cupid Sitting in a Tree

Cupid’s Wings

The Obligatory Meet-Cute

On the Five Act Structure

Getty’s Test

Now I Am Invisible!

Trilogizing

[Alternate Speech] “To gaze upon her mortal cheek”

How to Kill a Vampire

“I Do Not Lie”

If You Wanted Mary Poppins…

The Intrusion of Grace

SECTION 2. THE CUTTING ROOM FLOOR

[Extended Scene] Act II, Scene 1 – Four Rhyming Lovers

[Extended Scene] Act II, Scene 1 – Pinching Scene

[Alternate Scene] Act III, Scene 4 – Vanity, Vanity

[Extended Speech] Act III, Scene 4 – Perfidious Dagger

[Alternate Scene] Act IV, Scene 2 – All You Who Witness

[Deleted Scene] Act IV, Scene 4 – How Long Have I Been Here?

[Deleted Soliloquies] Act IV, Scenes 2-4 – In Heaven and In Hell

[Alternate Scene] Act V, Scene 2 – Four Lovers’ Fate (Psyche)

[Alternate Scene] Act V, Scene 2 – Four Lovers’ Fate (Cupid)

[Deleted Scene] Act V, Scene 2 – O! Give Him Back To Me!

Performances: FAQ

Copyright: FAQ

PART ONE: INTRODUCTION

Of Shaw, Shakespeare and Scholars

George Bernard Shaw—besides being known for his witty dialogue and torture of the common quotation mark—was

infamous for writing Introductions and Afterwards defending the plots of his plays, which Introductions and Afterwards were often double the length of the plays themselves.

Conversely, William Shakespeare wrote no Introductions to his plays—seems to have written nothing at all except his plays, and even in his plays, disdained to write such helpful things as stage directions.

Which has resulted in the gainful employment of otherwise unemployable Scholars who have filled up Shakespeare’s shocking lack of exposition with shelves and shelves of nothing but exposition—some of which, in their excitement, even expose that the Scholars don’t believe that the man they’re writing about wrote anything at all!

Fortunately, I am no Shaw. Unfortunately, I am also no Shakespeare.

But if the Scholars will excuse the presumption on their provenance, this Snyder would like to pull back the proverbial curtain and give the reader a glimpse into the writing and rehearsing of Cupid and Psyche, from 2008 to 2013.

The Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Quarto

But what is a “Bad Quarto?”

In 1603, the most famous “Bad” (that is to say First) Quarto of Hamlet was published.

The contents of the book itself—printed cheaply on folded paper cut in fourths—were not, alas, in the least bit salacious. (Whereas a “bad Quarto” version of Fifty Shades of Grey might be considered both morally and grammatically objectionable.)

No, what’s “bad” about the Bad Quarto of Hamlet is that the script is nearly unplayable. The language is trite. The characters thinly drawn. In fact, the first draft of the Greatest Play Evah is really just awful.

(Which should hearten playwrights everywhere. There’s nothing so happy as seeing a genius fail.)

Scholars have developed two major schools of thought to answer why this might be so:

The first suggests that the Bad Quarto wasn’t published by Shakespeare at all. Rather, the Bad Quarto, they hold, was pirated by an entrepreneurial spear carrier looking to make some extra cash (as entrepreneurial spear holders are apparently wont to do).

The argument for this lies in the fact that most of the scenes wherein tertiary “guard” type characters are present line up nearly word for word with later editions, while those scenes wherein our mystery actor might have been scribbling away backstage are considerably less accurate.

For example, compare “To be or not to be” here. (And then laugh uproariously at Rowan Atkinson’s revision here.)

Another school of thought, put forth most recently by Steven Urkowitz in his essay, “Shakespeare’s Revision of ‘King Lear’” (Princeton Essays in Literature, 1980) suggests that all of the First Quarto editions of Shakespeare’s plays were likely first drafts; were, in fact, working scripts.

That is to say: the Bad Quarto wasn’t bad; it was just good enough to throw on the stage.

And the second draft—that is, the Second Quarto—was a little bit better.

And then Shakespeare got the chance to tinker with it again, and out came the First Folio.

And then just one more quick revision, and voilà: Folio part Deux.

And scene.

It’s in this second spirit that you, dear Reader, are encouraged to enter into this edition, for you to judge the worthiness of this first Quarto.

Writing in Verse

The first question anybody asks me—after, “Who are you?” and, “Why are you staring at me?” is: “So, is it hard to write in verse?”

The answer to which, at least for me, is: “Nope.”

Now, that’s not a universal answer, in the same way that if you asked me if it was easy to play the Bach Cello Suites, I’d laugh hysterically in your face and then run far away, while if you asked Yo-Yo Ma the same question, he’d point you to his CD.

However, one might wisely point out, Yo-Yo Ma has had decades of practicing the cello, while I’ve only ever picked up my brother’s violin twice in my life. To which I’d nod enthusiastically and answer: “Exactly.”

In Bed with Billy Shakes

My first introduction to Shakespeare was in third grade.

I had just spent the previous year learning Everything There Was To Know About Dinosaurs (by which I mean I had looked studiously at the pictures of every available dinosaur book in our public school library), and therefore felt that I ought to challenge myself somehow.

There in the third stack of books from the back, I found a copy of the Complete Works of Shakespeare—a name that had somehow trickled down even to my nine-year-old mind. So, full of self-importance, I checked it out.

Like any girl of a romantic persuasion, I delved first into Romeo and Juliet, and having conquered the entirety of Western Literature, returned it. (They had just gotten in a few more dinosaur books.)

The following year, however, I came to the horrifying realization that the Complete Works of Shakespeare that I had read…had been a fake. Some nefarious person had in fact “translated” the playwright’s words into “modern language” and left it on the shelf for unwary third grade girls to find.

Infuriated at the outright hypocrisy and flagrant deceit inherent in the public school system, I marched to the local library and got out the Ridiculouʃly Olde ynd Oryginall Text of Master VVilliam Shakeʃpeare’s Compleat Plays (with Footnotes) and re-read Romeo and Juliet.

I finished the play.

Closed the book.

And reopened it.

Unfortunately, this second foray into Shakespeare’s works didn’t last quite as long, since I decided to try out Macbeth late at night during a thunderstorm, and there was a particularly loud lightning crash just as the Three Witches started speaking (aka, page one), and I screamed and threw the book across the room.

However, all of this is to say that I had the great good luck to meet Mr. William Shakespeare outside the often unfortunate confines of the classroom where his works are taught with all the excitement of Introduction to Tax Returns.

Even more, my mother snuck me in under a complex set of circumstances to see a production of my beloved Romeo and Juliet between third and fourth grade. While I’ve no idea from my now professional opinion whether the show was any good, my nine-year-old self remembers how funny the Nurse was, and how Juliet’s tomb was revealed below the stage, and how everything was just as it ought to be.

After that, Shakespeare kept popping up in my life—from a really terrific version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Sterling Forest Renaissance Festival, to our obligatory study of Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth, and Othello in high school (where I did my level best to volunteer for all the meaty roles, and my teachers, desperate for anyone to participate, let me play them), and finally to playing Feste the Jester in Twelfth Night in college.

How Not To Be Dun Edumicated

Somewhere in high school, I became really fascinated with structured poetry. I had just purchased a rhyming dictionary which included front material that listed different forms—from the mind-boggling difficult sestina to the jaunty villanelle.

By this point, I’d tried my hand at a few sonnets, both Elizabethan and Petrarchan, because it was one of the only forms of poetry that the blasted public schools actually taught us.

Much of my poetry learning was covert, smuggled between other students painfully reading out bits of Hawthorne and Dickens, I’d flip open to exciting things like Byron and Tennyson and the confusingly spelt e. e. cummings who did nasty things to the English language and got away with it.

However, as for what we were taught, no matter how talented the English teacher—and I’ve had some really terrific English teachers—poetry lessons went something like this:

1) We do not have the time, children, to teach you poetry.

2) Therefore, we shall teach you only those which even we cannot escape: which is Beowulf, and the Rime of the Ancient Mariner, and some Edgar Allen Poe, with a touch of Chaucer, and if you’re lucky, some Harlem Renaissance. None of which, although it looks like poetry, is poetry. Because it is Literature

. You will also read the same book by Dickens. Twice.

3) You will be forced to read the Songs of Innocence/Songs of Experience and to Understand Their Symbolism. Which is a Useful Skill, and—more importantly—one that can be tested.

4) Because, children, poetry is essentially Useless, and Of The Past (which we are not—and which is why we will give you soul-destroying “modern” anti-heroic books to read To Improve Your Minds).

5) However, if you must know something about poetry, it is this:

Poetry rhymes.

Except when it doesn’t.

Which non-rhyming poetry is infinitely better than rhyming poetry, because it is Modern, and everything New Is Good.

Cupid and Psyche

Cupid and Psyche